You've decided to invest in your brand or website. You've found a studio you trust. Now comes the part that trips up most business owners: the brief.

A design brief is the document that tells your creative team what you need, why you need it, and what success looks like. Get it right, and the project moves faster with fewer revisions. Get it wrong, and you'll spend weeks circling back to questions that should have been answered at the start.

The good news? You don't need to be a designer to write a strong brief. You just need to know what matters.

Why the Brief Matters More Than You Think

Design studios can't read minds. They can study your competitors, research your industry, and bring years of expertise to the table. But they can't know what's in your head unless you tell them.

A brief does three things:

- It forces you to clarify your own thinking before the project starts.

- It gives the design team a clear target to aim for.

- It creates a shared reference point when decisions get difficult.

Without a brief, projects drift. Feedback becomes vague. Rounds of revisions multiply because nobody agreed on the destination.

What Belongs in a Brief

You don't need a 20-page document. You need clear answers to the questions that actually shape the work.

The Problem You're Solving

What's broken? What's missing? What opportunity are you chasing?

Maybe your current website looks dated and you're losing credibility with potential clients. Maybe your brand no longer reflects who you've become as a company. Maybe you're launching something new and need to make a strong first impression.

Name the problem. Be specific. "Our website feels old" is a start. "Visitors leave our homepage within 10 seconds because they can't tell what we do" is better.

Your Goals

What does success look like six months after launch?

This could be more inquiries, higher-quality leads, a shorter sales cycle, or simply feeling proud to send someone to your website. Quantify where you can. "Increase contact form submissions by 30%" gives the team something to design toward.

Your Audience

Who are you trying to reach? What do they care about? What objections do they have?

The more specific, the better. "Small business owners" is too broad. "Service-based business owners with 5-15 employees who've been burned by agencies before and want a more personal experience" tells the designer exactly who they're speaking to.

Your Brand (If You Have One)

If you have existing brand guidelines, share them. Logo files, color codes, fonts, tone of voice documents. If you don't have formal guidelines, share examples of how you've presented yourself in the past. Even a collection of social posts, proposals, or email signatures helps.

If you're starting from scratch, that's fine too. Just say so.

What You Like (and What You Don't)

Collect examples. Screenshots of websites you admire. Brands whose visual style resonates with you. Competitors who are doing it well.

Just as useful: examples of what you hate. Knowing you despise cluttered layouts or aggressive sales copy saves everyone time.

A few visuals in a shared folder tells a designer more than a thousand words of description. This approach helps communicate ideas visually when themes are difficult to describe in words alone. [Source: Creating the Visual Design, Webflow]

Timeline and Budget

Be honest about both. If you have a hard launch date, say so. If your budget is fixed, share the number. A good studio will tell you what's realistic within those constraints.

Hiding the budget doesn't get you a better deal. It just wastes time while everyone tries to guess.

Decision Makers

Who needs to approve the work? How will feedback be collected? Will one person be the point of contact, or will a committee weigh in?

Projects with clear decision-making move faster. Projects where every stakeholder gets a vote on every detail stall.

How to Gather the Information

You don't have to write everything yourself.

Talk it out. Schedule a call with your team and record it. Explain the project as if you were describing it to a friend. Your phrasing during conversation is often clearer than what you'd write under pressure. [Source: The Who and What of Creating Content, Webflow]

Ask your customers. What made them choose you? What almost stopped them? What do they wish they'd known sooner? Their words belong in your brief.

Start rough. A bulleted list of topics is enough to begin. You don't need polished paragraphs. You need honest answers.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

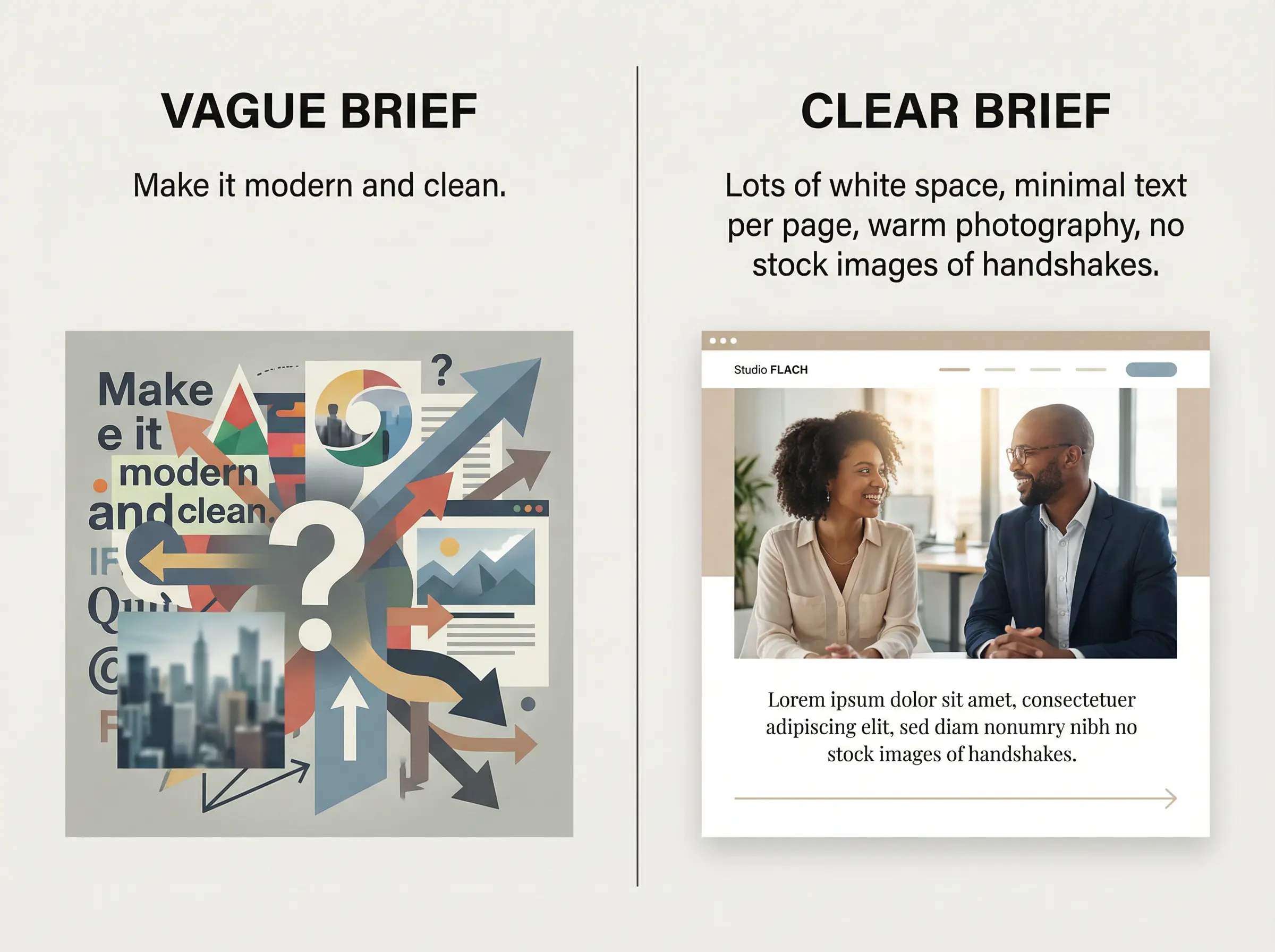

Being too vague.

"Make it modern and clean" means something different to every designer. Instead: "We want lots of white space, minimal text on each page, and photography that feels warm rather than corporate."

Skipping the why.

Requests without context lead to misaligned work. Don't just say "add a testimonials section." Explain that prospects frequently ask for references, and you want social proof visible before they reach the contact form.

Overloading with opinions.

There's a difference between useful direction and designing by committee. Share what you need to achieve. Let the experts figure out how.

Waiting until the end to mention constraints.

If the CEO hates blue, say so on day one. If the copy must be approved by legal, build that into the timeline. Surprises late in a project cost everyone.

The Payoff

A strong brief doesn't guarantee a perfect project. But it dramatically increases your odds.

You'll spend less time in revision loops. You'll make faster decisions because you can check them against the goals you defined at the start. And you'll end up with work that actually solves the problem you hired someone to fix.

The best design partnerships are built on clear communication. The brief is where that starts.